In August I wrote a blog post moaning about (some) medics and epidemiologists relying only on poor quality randomised controls when considering whether wearing an FFP2 mask offers more protection than a surgical mask. Little did I know that a group of scientists/mathematicians that included Nassim Nicholas Taleb were also grumpy about this. Taleb is known as the author of the black swan theory – and the book of the same name that I started and found interesting but did not finish.

Blog post of the 32,524th best academic on the planet!

I would like to take a break from being rude about university league tables to talk about a league table that is (too) good for my ego. This is of publishing academics and ranks me at 32,524 (data here). Being 32,524th may not sound impressive but the world’s population is over 7 billion – admittedly most of the 7 billion don’t publish academic papers. It also may be highest rank of anyone in my School at Surrey (but not the highest rank of anyone at Surrey). It is also higher than my sister’s rank*.

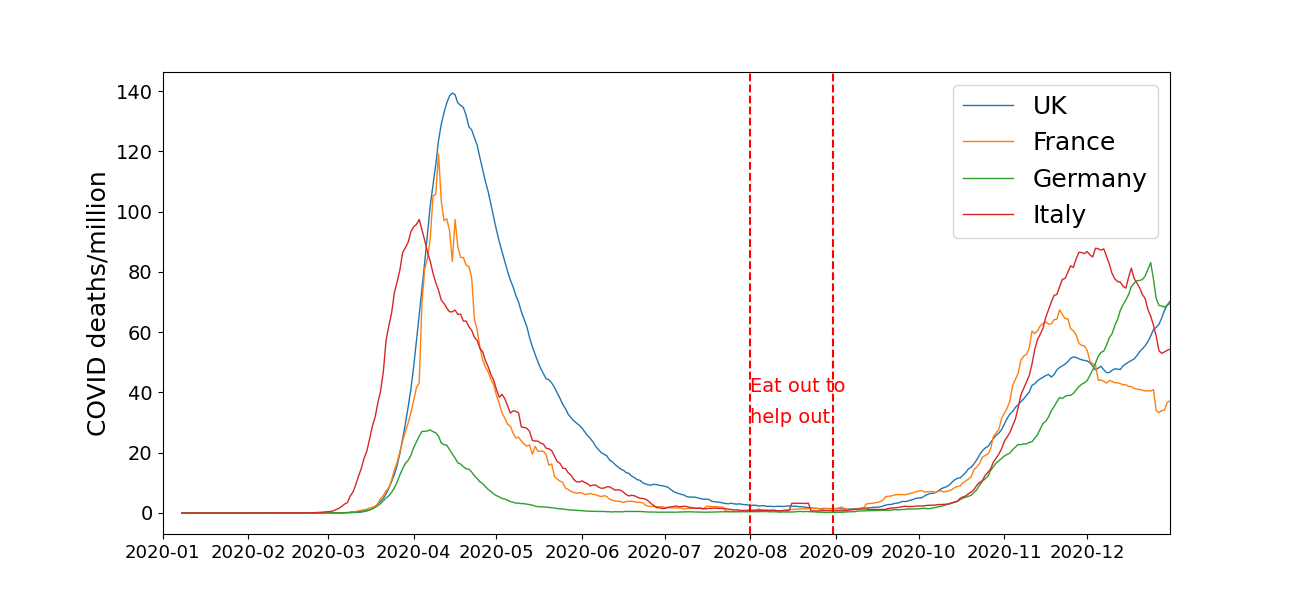

Bad graphs and bad epidemiology

The graph above is a bad graph** – it is a replot (as original will be copyright of The Spectator) of a graph in The Spectator article Did Eat Out to Help Out rekindle Covid? A look at the data, by The Spectator‘s editor Fraser Nelson. Rishi Sunak’s Eat out to help out scheme ran for the month of August 2020, and in the article Fraser Nelson (a politics and history graduate) decides to “look at the data” and tell professional epidemiologists why they are analysing this epidemiological data incorrectly. This demonstrates either impressive self-confidence or eye-brow-raising-arrogance, depending on how sympathetic you are to Mr Nelson.

University league tables are cargo-cult science, I am on a quixotic quest to convince The Guardian of this

Every year The Guardian publishes a new league table of universities. This year St Andrews is deemed the best university in the UK. There are so many problems with these league tables I am not sure where to begin*, and prospective students and their parents use them to inform life-changing decisions, so this matters. As an ex-admissions tutor, this bothers me, so most years when the new league table comes out, I write a polite letter to The Guardian.

Use, abuse and avoidance of models in science, economics and medicine

Last week I attended a meeting in Cambridge: the 7th Edwards Symposium – New Paradigms in Soft Matter and Statistical Physics. I even chaired the last session. It attracted a diverse range of attendees. As an example: As head of a research group in my University I am in charge of a £7,000 group budget. A speaker in the session I chaired – Jean-Phillipe Bouchard – is Chair of Capital Fund Management, which controls roughly €7,000,000,0000 of investors money. As I said, diverse range of attendees.

Combining data on the filtration efficiency of masks, with epidemiology studies of mask use

The previous post was perhaps a bit of a moan about epidemiologists and medics focusing on randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies, to the exclusion of absolutely every other study. This was in the context of using masks to reduce the probability that you catch COVID-19. But moaning is not very constructive. A better approach is to say: OK so epidemiologists are not combining epidemiology data with other data, but there is nothing to stop you doing this. So what can be done if data from epidemiology studies are combined with data of other types?

We all have blind spots, but maybe some are bigger than others

A question for you. It concerns mask wearing to prevent infection with COVID-19. Which do you find the most convincing evidence for wearing an FFP2 mask as opposed to a surgical mask?

- A study of 500 surgical mask and FFP2 wearing healthcare workers in which about 100 of them became infected with COVID-19. In other words quite a small study of people becoming infected.

- Studies of masks that show that an FFP2 reduces the dose by around 95% while for masks it is typically in the range 40 to 60%.

There is no real right or wrong answer here. Personally, I would vote for 2. as a study of 500 people, only 100 of whom became infected is pretty small. Whereas I assume that the lower the dose you inhaled, the lower the risk. So I am all for lowering the potential dose, and if you tell me by switching from surgical masks for FFP2-rated masks I can reduce the dose by about a half, I will do that. But I am nobody’s idea of one of “world’s most eminent scientists” and they went hard for option 1., completely passing on 2.

Web app for simulating a von Karman street

In the autumn I have some new teaching: a small project to simulate a problem — von Karman streets — in the physics of fluid flow (see earlier post). I will be showing the students how a simple Lattice Boltzmann code can simulate a fluid flowing past a cylinder, and creating what is known as a von Karman street of vortices downstream of this cylinder. The code is on github, and works great on linux machines. In particular it can show the flow around the cylinder evolving in realtime as the simulation runs. This is useful as you can see straightaway – while the simulation is running – if vortices are forming and being shed from the back of the cylinder*.

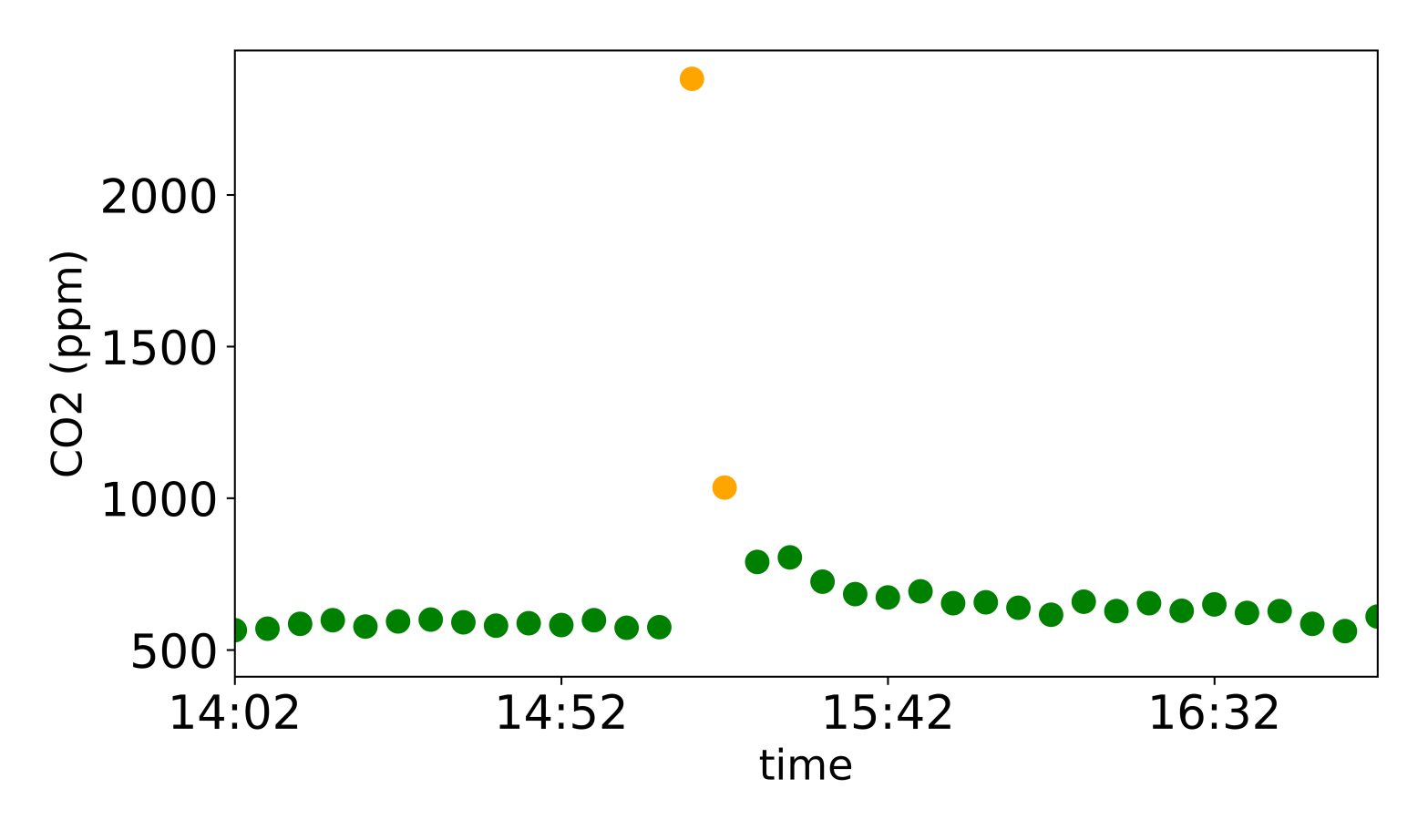

The case for induction hobs in kitchens

Just before lockdown I had a new kitchen installed, complete with a new oven and stovetop. A friend has also just had a new kitchen installed. Both lovely kitchens but I have a stove with traditional gas burners, while he went for induction hobs. To be honest I didn’t think about this much, my old stove had gas burners so I got new ones.

Viruses to the rescue?

Viruses have a bad press, and this is not surprising. COVID-19 is caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2 and the pandemic is estimated to have caused at least 15 million deaths. But our planet Earth hosts enormous numbers of viruses and not even one in a million infects us humans, it is just that these less than one in a million viruses are the ones we mostly care about. So 99.999% + of Earth’s viruses infect other organisms. When they infect us and make us sick that is bad but when they infect an organism we don’t like that could be good.