I started this post on the Boeing 777 whose left wing is in the foreground of the picture above. The flight was from San Francisco to London. It took off in the evening, so we got to see a stunning sunset with a beautiful blood red sky. In the plane, as we were so high up, the view of the sun and backlight clouds was amazing.

I started this post on the Boeing 777 whose left wing is in the foreground of the picture above. The flight was from San Francisco to London. It took off in the evening, so we got to see a stunning sunset with a beautiful blood red sky. In the plane, as we were so high up, the view of the sun and backlight clouds was amazing.

Standing out from the crowd, three points at a time.

I am writing this during the second of the three visits to San Francisco airport I will be making this week. A Singapore airlines plane has just taken off, and a Jumbojet is taxing past the window in front of me. I am in San Francisco to visit a colleague at a research lab called Laurence Berkley National Laboratory (LBNL), and I squeezed in a quick visit to a university, Stanford, just south of here. California is a beautiful place, above is a view from LBNL which is on hills above San Francisco bay, and on the other side of the bay from San Francisco. The view is looking down and across the bay and you can see San Francisco itself on the other side of the blue water of the bay. Berkley is in the foreground this side of the bay. It is a beautiful view.

I am writing this during the second of the three visits to San Francisco airport I will be making this week. A Singapore airlines plane has just taken off, and a Jumbojet is taxing past the window in front of me. I am in San Francisco to visit a colleague at a research lab called Laurence Berkley National Laboratory (LBNL), and I squeezed in a quick visit to a university, Stanford, just south of here. California is a beautiful place, above is a view from LBNL which is on hills above San Francisco bay, and on the other side of the bay from San Francisco. The view is looking down and across the bay and you can see San Francisco itself on the other side of the blue water of the bay. Berkley is in the foreground this side of the bay. It is a beautiful view.

Bad crystals can be bad in many ways

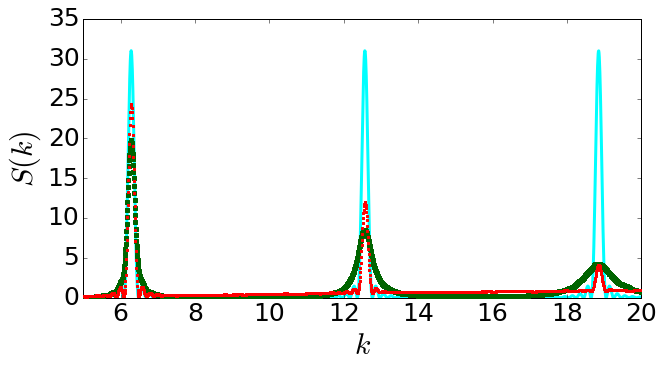

The standard way of studying the structures of crystals on atomic lengthscales, is X-ray diffraction. We fire X-rays at a sample and then detect the X-rays that bounce off the sample, as a function of the angle X-rays come out. This gives us what is called a structure factor, S(k), where k is called the wavector, which has dimensions of inverse length, i.e., m-1.

What effect do gravitational waves have on your body?

The biggest news in physics this year was the discovery of gravitational waves a couple months ago. Waves in time-and-space are cool, but they are very weak, the detectors measured a distortion in space of one part in 1021 (or 1 in 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000). That’s a small effect. On the one hand this is bad, as it made them very very hard to detect; the scientists on the LIGO collaboration must be experimental science ninjas and it still took them decades.

Following in the footsteps of both father and son

Different crystals have different symmetries and these can be read off from the structure factor. For example, a perfect single crystal with the symmetry called body-centred cubic (bcc) shows, when viewed from one angle, a structure factor with a set of sharp points including six arranged at the corner of a hexagon.

Bob’s birthday presents: a surprise party and magnetic monopoles

I was in Bristol on Thursday for a surprise 70th birthday party, of a friend a colleague, Bob Evans. About 40 of us waited at a restaurant to surprise him; he thought he was going there for a quiet dinner with his wife and few friends. This was a lot of fun. The next day there was a little symposium in his honour.

Taking the Doctor’s advice

Understanding how crystals start to form is tricky. We can’t see how it happens as crystals start off microscopic, it is very sensitive to pretty much every aspect of the experimental set up, and the standard theory (called classical nucleation theory) has basically zero ability to predict anything. So we are a bit stuck. But we don’t have the toughest job around, arguably the most complex, and hardest to understand, thing around is the human body, so perhaps the toughest job belongs to medics and biomedical scientists studying diseases.

Understanding how crystals start to form is tricky. We can’t see how it happens as crystals start off microscopic, it is very sensitive to pretty much every aspect of the experimental set up, and the standard theory (called classical nucleation theory) has basically zero ability to predict anything. So we are a bit stuck. But we don’t have the toughest job around, arguably the most complex, and hardest to understand, thing around is the human body, so perhaps the toughest job belongs to medics and biomedical scientists studying diseases.

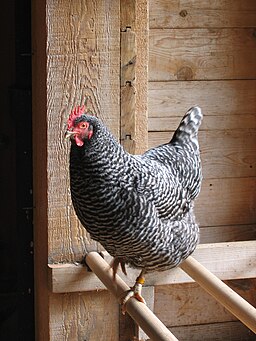

Chicken Little comes home to roost

Two years ago I wrote a blog post expressing amusement at Altmetric’s top papers for 2013. Now that Altmetric is rating a paper of mine #5 of 13,240 outputs (from the journal publisher and as of time of writing), it is clearly time for me revisit my position on Altmetric. Surely, anything that ranks my collaborators and me that highly must be on to something? Altmetric is software that collects references in the news media, blogs and on twitter, to a research paper, and then both provides links to them, and ranks the paper.

Two years ago I wrote a blog post expressing amusement at Altmetric’s top papers for 2013. Now that Altmetric is rating a paper of mine #5 of 13,240 outputs (from the journal publisher and as of time of writing), it is clearly time for me revisit my position on Altmetric. Surely, anything that ranks my collaborators and me that highly must be on to something? Altmetric is software that collects references in the news media, blogs and on twitter, to a research paper, and then both provides links to them, and ranks the paper.

The right tool for the job

I almost titled this post Daily Mail celebrates work of immigrants shocker but as they have written a pretty accurate article on work I am part of, that would be a bit ungrateful. Yesterday a paper came out in Physical Review Letters that I am really rather proud of, although I made only a small contribution to it. Most of the credit should go to Andrea Fortini, who discovered the effect the paper describes, and to Nacho Martin-Fabiani and Joe Keddie who did the experiments to show that it works in the real world too. Andrea found the effect in computer simulations. We also had help from collaborators in Lyon who made the particles Nacho used.

Reducing the risk of heart disease with the aid of Russian Roulette

It is almost always easier to borrow ideas and techniques from other fields than to reinvent them. A PhD student, another academic and I, are studying two competing processes. These are crystallisation into two different crystals, called alpha and gamma, of a small molecule called glycine. The formation of alpha and gamma appear to be mutually exclusive, one or the other forms, not both. Crystallisation is statistical, it is at least partly random, and they are irreversible, once a crystal forms it persists.