I am teaching second-year physics students computational physics; I have been doing this for 20 years. One of things that has frustrated me for a few years is students asking me to check results, when they just want to know if the answer is right or wrong. When I help students who ask this question I do try and take students through my reasoning. For example, if the correct result of the calculation is a Gaussian function, I briefly describe what a Gaussian looks like.

Soft manageable hair and protection from SARS-CoV-2

The physics of how masks work is a bit complex. Masks/face covering are air filters you wear on your face. They filter out droplets from the air you breathe in, or out. The mechanism for filtration is different for small and for large droplets. For small droplets it relies on diffusion of the droplets into contact with the fibres inside the mask, where the droplets stick and are filtered out of the air. Droplets in air are constantly bombarded with air molecules and this pushes them around at random: this random motion is called diffusion. For small enough droplets, these pushes are enough to cause significant numbers of the droplets to diffuse into contact with the fibres of a mask, during the short time the air and droplets spend crossing the thickness of the mask.

Working out if masks really work is hard

I am both teaching and shopping in a mask, and the UK is one of many governments that require people to wear masks in many situations. The obvious question is: Do masks work, i.e., reduce the transmission of SARS-Cov-2? Answering this question is hard, and to be honest we don’t have a good answer at the moment.

Thinking about breathing out

We breathe in and out all the time, without thinking about at all. But now is the time to think about how we breathe in and out. SARS-CoV-2 leaves an infected person in droplets in their breath, and the evidence is strong that a majority of infections start with someone breathing in the virus.

What one epidemiologist wants for Christmas

On Wednesday I watched a webminar given by the American epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch. It is part of a seminar series for physicists, on COVID-19. It was an interesting and sobering watch. I was struck by a comment Prof Lipsitch made in answer to one of the questions at the end of the webminar.

Evidence for the effectiveness of mask wearing

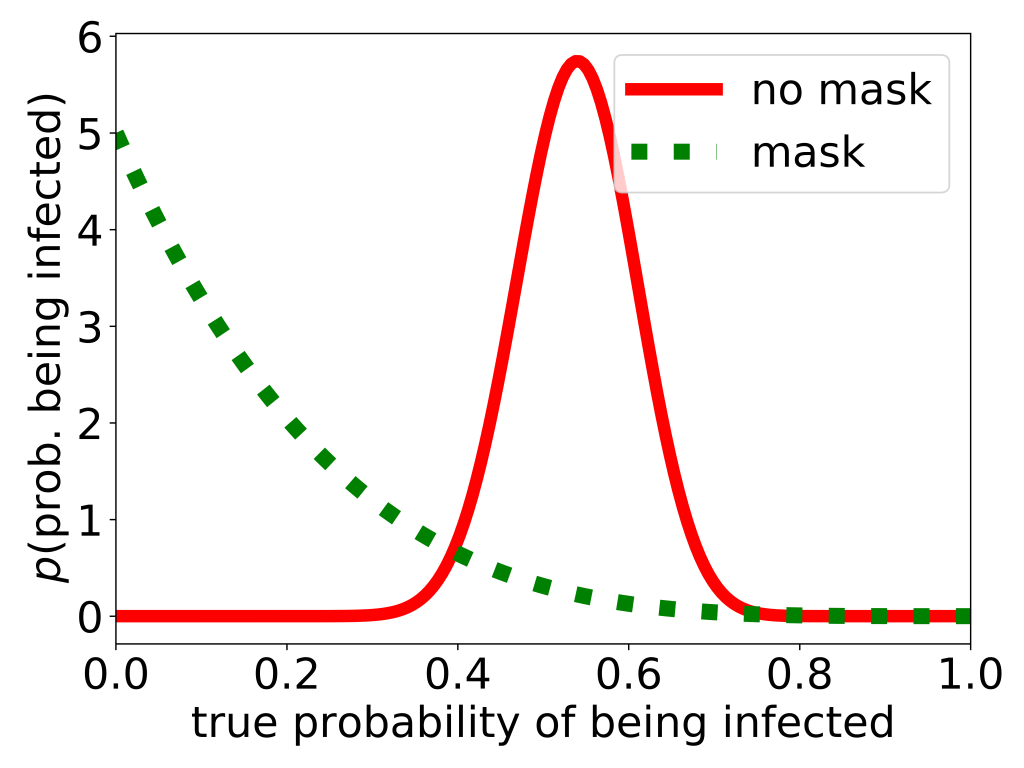

In August, 27 customers of a branch of Starbucks in South Korea were infected by one person. But none of the mask-wearing (it’s company policy*) employees were infected. One event does not provide a whole lot of data but it does allow us to take a stab at estimating how effective masks are. The plot above is an an attempt at that.

Masks and superspreaders

What is sometimes called a 90/10 or 80/20 rule or the Pareto principle, crops up a lot in life. If you doing are research, 90% of the best results come from 10% of your effort (sadly it is typically not possible to work out in advance which 10%!). It also seems to apply to the COVID-19 pandemic. 80% of the infections come from from 20% of the infected carriers. As I talked about in the previous blog post, there are superspreading events, in which one infected person can infect tens of other people, in one day. At the other end of the spectrum, many infected people do not pass the virus on to even one other trticperson. With colleagues I am working on understanding how masks work, which leads to the question: Can wearing mask use reduce the number of these superspreading events?

No such thing as an average infected person

I am very struck by this quote from a paper measuring the concentration of corona virus (aka SARS-CoV-2) in swabs taken from infected people

Initial SARS-CoV-2 viral load is widely distributed ranging from 3 to 10 log copies/ml …

Jacot et al, medRxiv 2020

Note the log in the first sentence, the range is not from 3 to 10 — about a factor of 3 — it is from 103 to 1010 viruses per millilitre — a range where the top end is 10 million times the bottom end. In other words, some people at some times during their COVID-19 infection have ten million times as much virus as others do. On a log scale, the average is 106.5 ~ 3 million viruses per millilitre but some infected people have thousands of times more, while others have thousands of times less.

Minimal model of corona virus exposure

Transmission of the corona virus (aka SARS-CoV-2) is very complex, which is basically why it is so poorly understood. But in true theoretical-physicist style, a minimal model has been developed, by a guy called Roland Netz (who is a theoretical physicist in Berlin). It makes a lot of assumptions, and it is clear that there is lot of variability, between one infected individual and another and between one situation and another, so its predictions should be taken with a large pinch of salt. But in this post I will outline this minimal model.

Google Colab means that everyone can have a league table in which their University is top

This blog post combines/builds on two earlier posts: One where I looked at using Google Colab to host Jupyter notebooks for my autumn teaching, and one where I messed around with a Jupyter notebook that can generate a university league table with almost any university at the top. I have tidied up the league table generating Jupyter notebook and you should now be able to see it on Google Colab here and the spreadsheet it needs with the University data is available here.