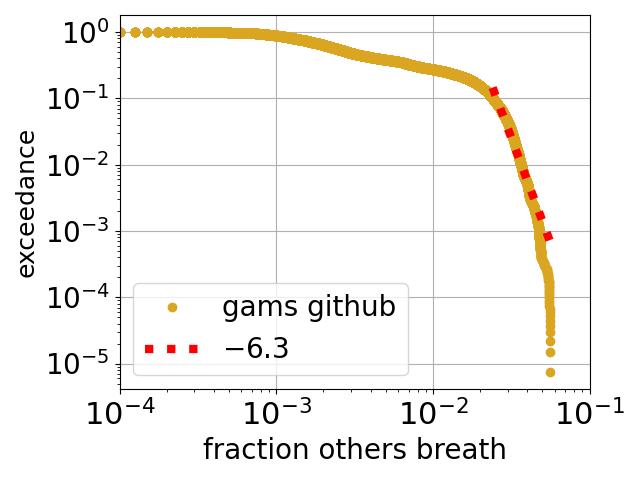

Above is plotted a slightly odd function called an exceedance, the y axis is the probability that the value on the x axis is exceeded. The data is from a large dataset of measurements of indoor air by a Chinese company called gams Environmental Monitoring*. The x axis is the estimated** fraction of air in the room that is second hand, i.e., has been breathed out by another person (or by you). For example, the probability is close to 0.1 = 10% for a value along the x axis of 0.03 = 3 %. So, for this dataset, about 10% of the time the room air is at least 3% second hand. Another way of approaching is to say that the median fraction of the air that is second hand is around half a %.

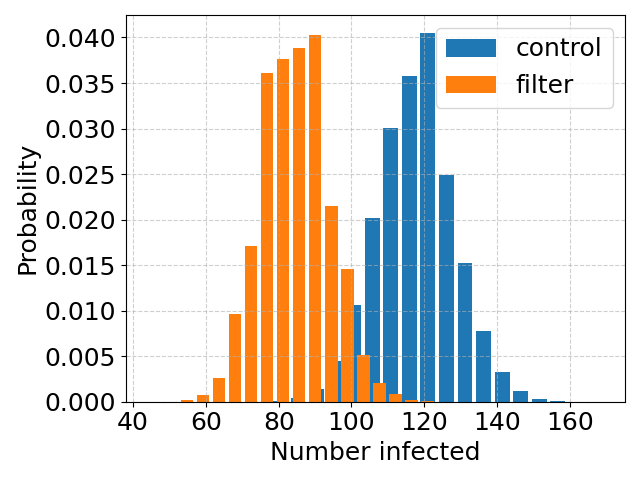

How many need to become infected, to declare air filtering a success?

This post is, basically, a part II to the previous post on the study of Brock et al. on the effect of installing room air filters, on COVID transmission in hospitals. Brock et al. found that the air filtering “was associated with a non-significant trend of lower hazard for SARS-CoV-2 infection”. The “non-significant” here is a bit sad. The study was of a total of 229 hospital-acquired infections and the conclusion was that this number is too small to draw a definite conclusion. So, how big a study do you need to come to a definite conclusion?

Minimising hospital-acquired COVID in Cambridge

Hospitals are full of both infected people, and very susceptible people – people whose immune systems are, due to age or illness, very weak. This is a terrible combination but unavoidable. And it is why it is important to try and minimise the spread of infectious diseases such as COVID, but also why it is hard to do this, especially for airborne diseases like COVID. With airborne diseases you can reduce transmission via (good, eg FFP2) mask wearing. But masks are not very comfortable, so a more palatable solution is to improve the quality of the air itself, either by improved ventilation (ie more fresh air), or by filtration. Brock et al. at Cambridge Hospitals recently (2024) published a study of the effect of air filtration on COVID transmission in hospital wards.

Back to the air conditioning units of Boeing 707 airliners

Above is avery pretty cartoon/schematic* of a virus MS2 that infects bacteria. I think it is used in proof-of-principle studies with viruses, as it is safer/easier/cheaper to work with than viruses that infect us. The virus can become airborne, which brings us to air conditioning units, which typically have filters as part of them. The filters can filter out viruses such as MS2 from the air.

Back in the early 1960s, an engineer called Proschan studied data on breakdown statistics of air conditioning units of early airliners. Now the most basic model for these statistics is that each unit fails at some constant fixed rate (i.e., probability per flight), and then the fraction still working after a given time decays exponentially with that time. Proschan realised that if indeed each unit had a constant failure rate, but that the units were heterogeneous in the sense that this rate varied from one unit to another, then the fraction still working would always decay more slowly than exponentially.

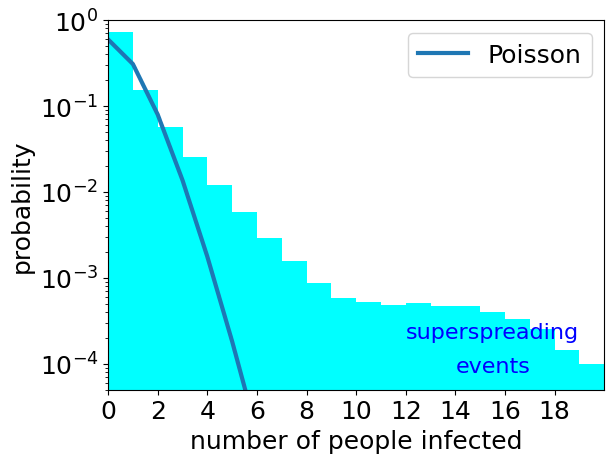

How common are superspreading events for COVID?

Although good systematic data are lacking there are observations of what are called superspreading events. These are single events at which many people become infected. An example from early in the COVID pandemic is the superspreading even at a choir practice in Skagit Valley (USA) where it is likely that 53 attendees were infected in one event. Transmission is a random process. So just by chance we expect sometimes one person becomes infected at an event, sometimes by chance two or three, or …. So we always would expect at least some superspreading events. But how many?

Self-destructing droplets, part N

For around a number of years* I have been fascinated by droplets that are in gradients (shown in the movie by a colour gradient of the background), and are an undersaturated solution so are dissolving. They have been some cool experiments done that see droplets zipping along gradients and dissolving as they do so, in particular by Hajian and Hardt. But it is a hard system to model and to understand.

Conservative and Labour politicians spreading misinformation they just don’t understand

Andrew Gwynne is a Labour MP and Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Public Health and Prevention in the current Labour government. He is spreading misinformation about COVID transmission on behalf of either civil servants or the NHS’s IPC (Infection Prevention and Control) cell. See this Bluesky post by Al Haddrell which has a letter signed by Gwynne and to an MP (Tim Farron) who was written to Gwynne of behalf of a constituent.

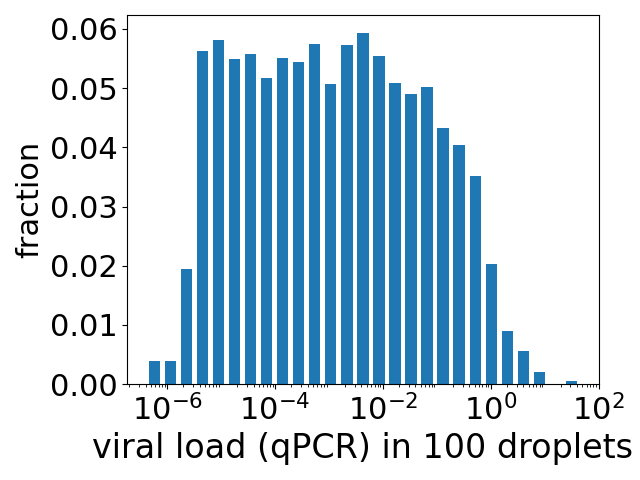

How much virus do you inhale during a few minutes chatting with someone infected with COVID?

The title seems a reasonable question to ask. If you are pretty close to someone and talking to them, then you are facing them and so more-or-less in the direct path of their exhaled breath. A single exhaled breath contains very roughly of order a few hundred aerosol droplets* (typically all of which are so small they are invisible). Depending on how close you are to someone you are talking to, the air you are inhaling may contain say 1 to 10% air they have breathed out. At a breath every few seconds then during a chat with someone you could inhale anywhere between tens and many thousands of tiny droplets that they have exhaled – a perhaps unattractive thought but this is what happens when we share the air with fellow humans. Something, we as social creatures, do a lot.

Does an infectious dose of a virus exist?

Maybe not. The basic model for the transmission of infectious diseases like COVID assumes that there is such a thing as an infectious dose of a virus, and that these doses act independently. By independently I mean that if you are exposed to one infectious dose, then the probability that you do not become infected is some probability, call it p, while if you are exposed to two infectious doses, then the probability that neither of them infects you is p2 — independent probabilities multiply. As 2 here is an exponent, the probability you avoid infection decreases exponentially with the number of these doses. This predicts a sharp – exponential – increase in the probability of becoming infected, with increasing amounts of virus.

We do not have data on infections in people, but we do have data on infections for cells growing in culture (ie growing in a petri dish or similar). And this exponential variation is not what is observed. See the figure above*. The data are the blue discs and are from the work of Jaafar et al.. The fit of an exponential function is shown as the green dotted curve. The fit is terrible.

The Welsh ambulance service declares a “critical incident” and still the NHS in Wales does not “follow the science”

A couple of days ago – 30th December 2024 – the Welsh ambulance service declared a critical incident. According to the Wales Online report, the head of the ambulance service, Stephen Sheldon said

“It is very rare that we declare a critical incident, but with significant demand on our service and more than 90 ambulances waiting to hand over patients outside of hospital, our ability to help patients has been impacted.”

Welsh (and English) hospitals are under great pressure from a “quad-demic” of flu, RSV, COVID and norovirus. Three of these diseases are transmitted across the air: flu, RSV and COVID. The fourth: norovirus, is food and waterborne. This pressure has prompted the introduction of both visiting restrictions and masking requirements in Welsh hospitals.

The visiting restrictions for Swansea’s hospitals near where my mother lives are here. If you follow the link you will see a large picture of surgical masks, so looks like visitors to hospitals will be handed surgical masks, to try and reduce the spread of flu (and RSV, COVID etc).