Early on in the pandemic, the aerosol scientist Jose-Luis Jimenez made available a Google Sheets implementation of the standard model for airborne disease transmission: the Wells-Riley model. This was a very nice idea, to provide a rational way to estimate the risk of transmission. The Sheets implementation is very open about the (many) assumptions made by the model, and it cites supporting literature. It is a good piece of work.

As Jimenez states in the Google Sheets “The most uncertain parameter is the quanta [of infectious doses of SARS-CoV-2] emission rates for SARS-CoV-2”. I think this is fair. It uses a value of 970/h for the rate at which an infected person emits doses of infectious virus. This is from work of Miller and coworkers on the Skagit superspreading event. And so “We do not think that this very high value should be applied to all situations, as that would overestimate the infection risk.”

So, what value to use? Modern qPCR can (semi?)-quantitatively assess the amount of virus in an infected person’s mucus/saliva. Takatsuki et al. did this for 690 infected people. Now, for the Wells-Riley model we do need to make some assumptions for the volume of aerosol particles a person breathes out, the volume of the room etc*.

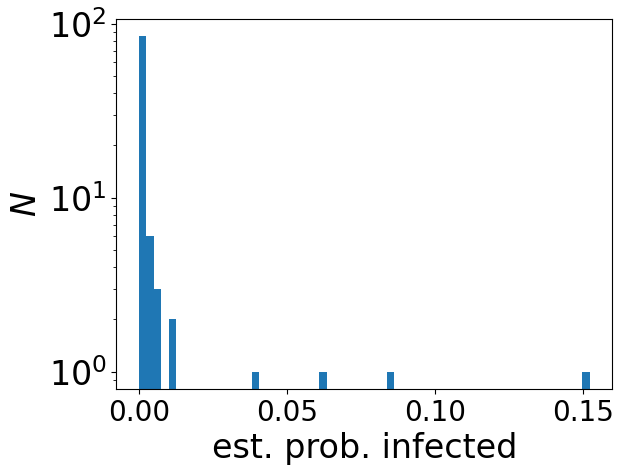

Having made these assumptions, I can sample 100 infected people from the 690 that Takatsuki et al. studied, and then estimate the probability of infection after 3 h in a poorly ventilated room** with this infected person. The histogram of these 100 probabilities of infection is above.

There is a very wide spread of probabilities. One of the 100 is estimated to have a 15% probability of infection, while most have an almost zero chance of infection. This follows directly on from the fact that some infected people have a million times more virus in their system than others***. Most infected people have a relatively very low amount of virus in their system, and the prediction is that if you share a room with one of these people, it is very unlikely that you will become infected.

To become infected, you almost certainly need to not only have the bad luck to share a room with someone who is infected, you also need the bad luck of them having an unusually high viral load. At least that is the prediction.

* I assume a person emits 106 aerosol droplets per hour, with a mean volume per droplet of 1 m3. The dose needed for infection is taken to be 10 viral particles. The room is assumed to have a volume of 100 μm3. The virus is taken to have an intrinsic decay rate of 0.62 /h, and the room is badly ventilated with just one air change per hour. A person is assumed to breathe in 1.56 m3/h. And this is for a 3 h stay.

** The Wells-Riley model is for transmission across a room, if you get close to, eg to talk to, the infected person, the risk will be higher.

*** Cumulative probability plot of the viral load from Takatsuki and coworkers’ data is in Figure 2 here.